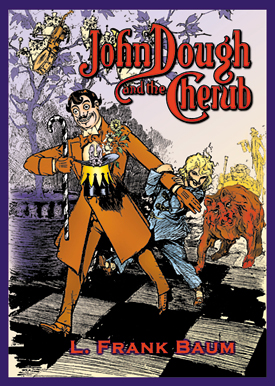

The first printing, in 1906, of John Dough and the Cherub opened with an unusual touch: a contest where readers under the age of 16 were asked to guess the gender of one of the book’s two protagonists—for the then considerable sum of $100. This also alerted readers to Baum’s latest literary experiment. Having written about a young character who switched genders, he would now try writing about a young character with no discernable gender at all, a remarkable experiment in children’s literature.

From all appearances, Baum had no thought of doing anything so radical when he first began the book, which opens with a retelling of the old folktale of the Gingerbread Man. Like any good living baked goods story should, the tale starts with a tantalizing description of an absolutely marvelous sounding bakery, where, thanks to a series of unfortunate events, a bottle of exceedingly precious Elixir of Life has been dumped into the gingerbread mix. (This sort of thing can happen even at the best managed and regulated bakeries.) The gingerbread mix, in turn, has been molded into a lifesize gingerbread man called John Dough, who, after a short stint in the oven, wakes to find himself alive and extraordinarily strong, with a remarkable gift for linguistics. (Elixirs of Life have many beneficial effects.) Only one small problem: a number of people want to eat him. After all, he smells fresh and delicious, and, as the previous holder of the Elixir, a certain Arab named Ali Dubh, knows quite well, eating John Dough will allow the consumer to gain marvelous powers. Not surprisingly, John Dough is less than thrilled at the thought of getting eaten, and thus leaps on a Fourth of July rocket, taking off to a fantastic world filled with magical islands.

(At the time, this was not the same world as Oz, but Baum, in a later attempt at cross-marketing, brought the characters from this book to Oz, and most Oz fans have generally followed his lead and decided that the various islands are, more or less, in the same world that Oz is. In the mysterious way that magic works, you know.)

On the magical islands: pirates (pirates!) saying “Avast there me hearties” in the proper pirate fashion; some delightful aristocratic folks who, apparently overinspired by the Arabian Nights, kill their guests once the visitors have run out of stories to tell; a lovely, innocent little princess; some rather unpleasant semi-human beings called Mifkits; a bouncing rubber bear; an executioner saddened that she has no one to kill; some freakish inventors; and Chick the Cherub, an Incubator Baby.

Incubators were still new, exotic items in the early 20th century, only recently adapted from ones used on chicken farms to save the lives of premature, sickly or fragile human infants. Many of these incubators, with said premature, sickly or fragile human infants still inside them, were displayed at public exhibitions to curious onlookers. I don’t know if Baum was aware that some medical practitioners strongly disapproved of this practice (it ended in the early 1930s, probably because, by that time, the novelty had worn off). But if he was not concerned about the impact that these public viewings might have on an infant, he seemed fascinated by the effect that an incubator might have on gender assignation, especially if the infant, like Chick the Cherub, had no other parenting or contact with humans.

Raised solely by the incubator, Chick the Cherub is a bright, cheerful and entirely healthy child, if perhaps a bit overcautious about eating only a very healthy diet. And, as a result of the Incubator parenting, almost completely genderless, to the point where Baum refers to Chick as “it” and “the Baby,” avoiding any use of “he” or “she.”

I say “almost completely” because despite Baum’s care at keeping Chick’s gender ambiguous, and John R. Neill’s equally careful attempts to give the child a gender neutral haircut and sloppy clothes that could be worn by either sex, I still read Chick as more boy than girl. I’m not sure if this is a failing on Baum’s part or mine, especially since I can’t point a finger at exactly what makes Chick “feel” male to me. But when I started writing the above paragraph, I realized that I was thinking “he,” and not for the convenience of the singular pronoun.

This gender ambiguity leads to some awkwardness with the writing. I don’t particularly care for the way Baum continually calls Chick “the Baby” or “it.” The word “it,” in reference to a human being, doesn’t just feel impersonal here, but actively alienating and repulsive. Chick simply has too much cheerful personality to be an “it.” And whatever else Chick may be, the Incubator Child is not a baby. Chick saves John Dough on several occasions, helps fly an airplane, firmly lectures John Dough on morality, and recognizes the significance of the final set of prophecies at the end of the book, bringing about the happy ending. No one questions Chick’s right to become Head Booleywag (the ruler who rules the King) of Hiland and Loland. And since no one is using “Baby” as either a nickname (despite my occasional urge to squeak, “Nobody puts Baby in the corner!”) or in a romantic sense, the word feels off. (Chick does embrace and kiss the young princess on the cheeks, but I don’t think we’re meant to read this romantically. They’re just saying goodbye.)

The Incubator Baby is not the only scientific development mentioned in this fairy tale: Baum also has an airplane powered by electricity, just three short years after the Wright Brothers’ first successful flight; a creator of industrial diamonds, and a gravity repulsion machine. (Okay, so the last isn’t quite standard in households yet.) Most of these, in direct contrast to the inventions in Baum’s earlier book, The Master Key, prove to be lifesavers for John Dough and the Cherub, a return to considerably more positive attitudes about scientific development.

And John Dough, despite his intelligence and erudition, certainly needs a lot of rescuing. Unlike most of Baum’s other unhuman characters, John Dough, whatever his physical strength, is surprisingly fragile, facing the constant threat of getting eaten, by the first human he converses with and everyone who later smells his wonderful gingerbread scent, by Ali Dubh, and most painfully, by the little princess.

The little princess just happens to be dying from some unknown yet convenient for the plot disease, wasting away a little bit each day. (Quite possibly from that famous 19th century literary disease, consumption/tuberculosis, which was a lot less pleasant in person than in novels.) John Dough’s gingerbread body, filled with the Elixir of Life, could save her if, and only if, he is willing to break off pieces of his body for her to eat. In these pre-blood transfusion and organ donor days, John Dough, who has already risked water, heights, rocks and Misfits to remain intact, is horrified by the idea—as horrified as the first time he encountered a human eager to eat him.

Chick the Cherub and Papa Bruin, the rubber bear, however, insist that John Dough must let the princess eat a part of him. If not, they will no longer be his friends. (Given that he has needed them to survive, this threat contains a hint of a death sentence.) Even this threat does not diminish John Dough’s fear of losing his hands or other body parts. Not until a few birds start eating him does he decide that he might as well allow the princess to eat him before other, less kindly creatures, consume him entirely. A delighted Chick and Papa Bruin agree to remain his friends.

The near blackmail puts this into heavy stuff for a children’s book, with a surprisingly realistic touch. John Dough’s reluctant response, coupled with the fact that he has only been alive for a few hectic days filled with people trying to eat him, is understandable, even moving. As it turns out, doing the right thing and sacrificing a part of himself for the princess helps prepare him for the method he will need to take to escape the Mifkits and eventually earn his happy (if somewhat rushed) ending.

One word of warning: the Arab villain is described in terms that, while typical of Baum’s time, could be considered offensive. It’s another sign that Baum, in general, did better when writing about worlds that were not his own.

Mari Ness experienced dreadful cravings for gingerbread while writing this post, and is off to go fill those needs now.

I remember reading that, after Baum submitted the first few chapters to a magazine editor for serialization, the editor insisted that he add a child to the story. That would explain why Chick shows up so abruptly after John lands on Phreex.

@nathan DeHoff

That does explain a lot – and (this is pure speculation on my part) – possibly Baum decided that if he absolutely positively had to have a child in the story, he might as well do something interesting and different with the kid.

A friend of mine (David Hulan, who is responsible for Books of Wonder’s ‘The Glass Cat of Oz’, half a dozen of Emerald City Mirror’s serialized stories, and two of the publication projects on my own websdite) agrees with you regarding the probability that Chick is in fact, a boy. He bases this on a very sound observation.

Although Baum’s girl heroes are brave, adventurous, even sometimes aggressive, and not at all weepy or wimpy, they are never mischevious. His boys quite often are (one needs only think of Tip’s prank to frighten Mombi by building a Pumpkinhead). Chick shows a definite talent for mischief which is not at all in keeping with a Baum girl.

Am much enjoying this series. Thank you for posting it.